The problem

Pharmaceutical pollutants are now routinely detected in rivers, lakes, coastal waters, soils and drinking water around the world.

These pollutants are increasingly harming our environment and posing growing risks to our health and economy.

Taking action is not straightforward. The risks of pharmaceutical pollution have been known for decades, but the systems that support pharmaceutical production, use and disposal are complex and deep-rooted in our society. A number of challenges continue to limit progress.

Failure to address pharmaceutical pollution undermines the resilience and long-term future of organisations across the healthcare and pharmaceutical sectors.

These organisations face growing financial, regulatory, operational and social pressure to reduce their pollution footprint and become environmentally sustainable.

Without deliberate intervention across the pharmaceutical lifecycle, emissions to the environment and the risks associated with this will continue to rise. The demand and supply of medicines is rising as global populations grow and age, as the burden of chronic disease increases, and as people gain better access to healthcare.

Leading international bodies now recognise the growing risks of pharmaceutical pollution and have called for action, for example:

By 2030, the global pharmaceutical market is expected to reach a value of US$ 2.35 trillion. Data taken from Grand View Horizon. Includes revenue data to 2024 and forecast data from 2025-2030.

Risks to Environmental and Human Health

Environmental health RISKs

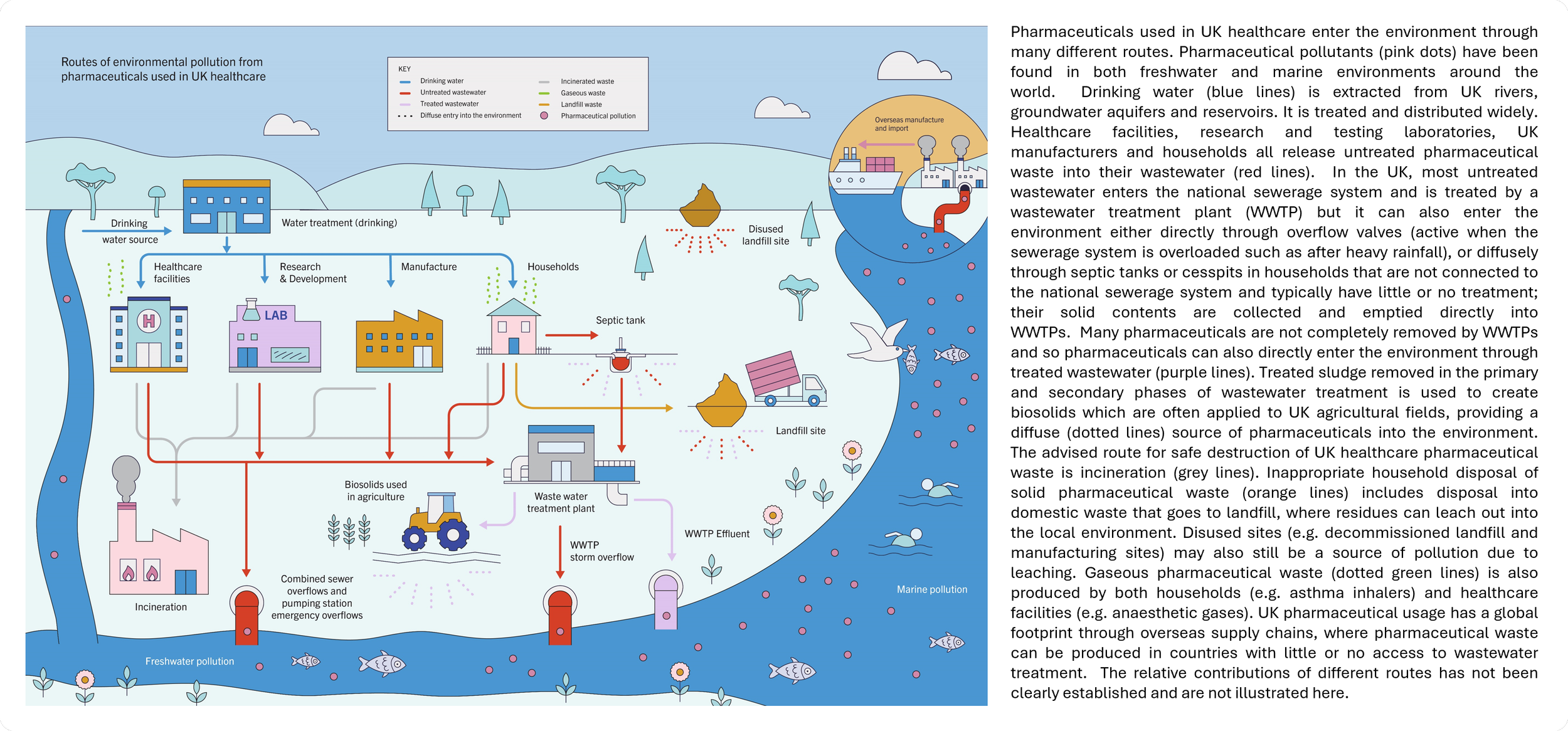

Pharmaceuticals are biologically active chemicals. They are designed to act at very low doses in order to prevent side effects in our bodies. Many of their physiological targets are also conserved across species so are present in wildlife. As a result, even trace concentrations in the environment can affect the health, behaviour, reproduction and survival of wildlife. Pharmaceuticals enter the environment via many routes (as shown below for the UK).

Some pharmaceuticals are broken down quickly, but some can persist and remain biologically active for a long time. Some commonly used pharmaceuticals are broken down quickly but are constantly discharged into the environment so their impacts are essentially the same as persistent compounds.

A 2022 study of 258 global waterways detected pharmaceutical pollutants on every continent (including Antarctica). More than a quarter of sites tested were found to contain at least one pharmaceutical pollutant at levels considered unsafe.

Figure and text adapted from our research paper published in the Lancet Planetary Health.

There are many knowledge gaps in our understanding of how all of the pharmaceuticals released into the environment impact on the hundreds or thousands of different species in any one ecosystem. This is made more complicated by the fact an increasing number of other chemicals are also present in these aquatic environments - these can interact with the pharmaceuticals and change their activity.

However, there is increasing evidence of negative impacts, including:

Oestrogenic compounds disrupting reproduction in fish. For example compounds originating from contraceptive and hormone therapies (see 2004 report).

Antidepressants causing altered behaviour in aquatic species. Exposure has been shown to reduce their risk-avoidance behaviours and increase their susceptibility to predation (see 2016 and 2025 research papers).

Anti-inflammatories causing renal failure in vulture populations. Gyps vulture populations in India were almost completely eradicated due to feeding on the carcasses of cattle treated with the drug diclofenac. This led to an estimated 104,386 annual human deaths in the following 5-year period, with a societal cost of $69.4 billion per year (see 2004 and 2024 research papers).

Human health RISKs

Pharmaceutical pollution is also a growing concern for human health, although there are also huge knowledge gaps in our understanding of these risks too.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR): Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is when microbes (including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites) become resistant to the medicines that have been developed to target them. AMR is a major global health threat that is one of the greatest risks to global public health. Between 2025 and 2050 AMR is expected to lead to 39 million deaths (one every 3 minutes) (see 2024 research paper). Antimicrobials and other pharmaceuticals in wastewater, surface waters and soils contribute to the emergence and spread of AMR (see 2025 research paper).

Chronic low-dose exposure: People are exposed to pharmaceutical residues through drinking water, crops grown in contaminated soils and recreational waters. Levels of exposure are usually below safe therapeutic doses, but we do not yet understand the risks associated with this (see 2019 report and 2024 research paper). Few research studies have examined pharmaceutical accumulation in the human body and the long-term health implications of continuous, low-dose exposure to complex mixtures of chemicals (including pharmaceuticals).

A Number of Challenges Continue to Limit Progress in Addressing these Risks

The environmental and human health risks of pharmaceutical pollution were initially raised decades ago, yet little progress on addressing these risks has been made since then. The issue of pharmaceutical pollution is multifaceted, dynamic, and uncertain in nature, with a complex range of interconnected social, economic, and environmental drivers. Some of the major factors limiting progress are:

System-level complexity. Pharmaceuticals are deeply-embedded within modern healthcare and society, and the systems that govern their production, use, and disposal are complex and highly resistant to change. There is no simple solution.

Competing priorities. Across the pharmaceutical life cycle, different organisations have many different needs, interests and priorities. This makes it difficult to agree on solutions and take collective action.

Poor accountability. The issue of pharmaceutical pollution spans the healthcare, industry and environmental sectors but is not a priority for any, so no one sector is taking responsibility for leading action.

Fragmented evidence. There are many knowledge gaps and datasets that are available are often highly technical, making them difficult to consider in operational and policy decisions.

Low visibility and awareness. Pharmaceutical pollution is physically invisible in day-to-day operations and the issue is poorly recognised outside specialist circles.