What is a systems thinking approach?

Essentially, it’s looking at the bigger picture and how everything fits together.

When we look at a problem, we can usually identify its direct causes and effects. But often the problem has in fact come about from a complex, interconnected and dynamic system of social, economic, political and cultural factors that are upstream of these causes, and the effects are likely to be felt beyond the immediate downstream ones that we can easily identify. This means that when trying to identify solutions, we need to consider these wider factors, otherwise it is unlikely that the problems will be effectively addressed in the long-term. A systems thinking approach to change takes this bigger picture into account, by looking at the societal systems within which problems lie.

For example, consider a community whose drinking water sources are contaminated with bacteria causing diarrhoeal diseases. We can solve their gastrointestinal problem in the short-term by treating them with antibiotics, but that isn’t going to be effective in the long-term unless we address the broader factors contributing towards water contamination. These could be factors that seem very distant to the problem, for example political decisions that alter land management practices (which in turn affect water systems) or changes to financial investment strategies that increase social inequalities (thereby increasing health and susceptibility to infection, or access to clean water). Addressing these factors is far, far more time consuming, expensive and complicated than giving an antibiotic, but the problem is unlikely to go away unless we do so.

At the Pharma Pollution Hub, we are applying this systems thinking approach to the problem of pharmaceutical pollution. To find solutions that reduce the environmental impacts of pharmaceuticals used in UK healthcare, we first need to understand the wider system of factors driving this. We initially mapped out the UK healthcare pharmaceutical system, by looking at the entire pharmaceutical life cycle. We then examined the system in more detail to understand the stakeholders, process and influences driving pharmaceutical use and pollution all the way from the design, manufacture and distribution of pharmaceuticals, to their procurement, prescription and disposal, to wastewater treatment, environmental monitoring and management.

This analysis showed that each stage of the pharmaceutical life cycle affects the impact that pharmaceuticals have on the environment and offers potential intervention points to address the problem. For example, pharmaceuticals could be designed (or re-designed) to degrade faster in the environment, their manufacturing processes could be optimised to reduce the level and toxicity of by-products, the distribution of pharmaceuticals could be more efficient to reduce the amount wasted through expiry. Within the healthcare sector, decisions are made on which pharmaceuticals to approve, which ones to procure, which ones to prescribe – these decisions could take into account the environmental impacts of a drug as well as its health and financial impacts. Wastewater treatment could be improved to remove a greater proportion of pharmaceuticals, and our rivers and lakes could be regularly monitored for more effective management and environmental protection regulation.

Many of these interventions are either underway, under consideration or have tried and failed. Many offer benefits to one sector but challenges to another. Many have the potential to reduce pharmaceutical pollution but would likely increase carbon or water footprints, or be very expensive in the short-term. This is a complex system, and any one of these solutions implemented at an individual level is unlikely to dramatically reduce the overall environmental impact of pharmaceuticals used in healthcare. But if we co-ordinate our efforts across the system, by considering sustainability trade-offs, identifying co-benefits wherever possible, and supporting organisations to make long-term changes, our system can evolve to become more sustainable.

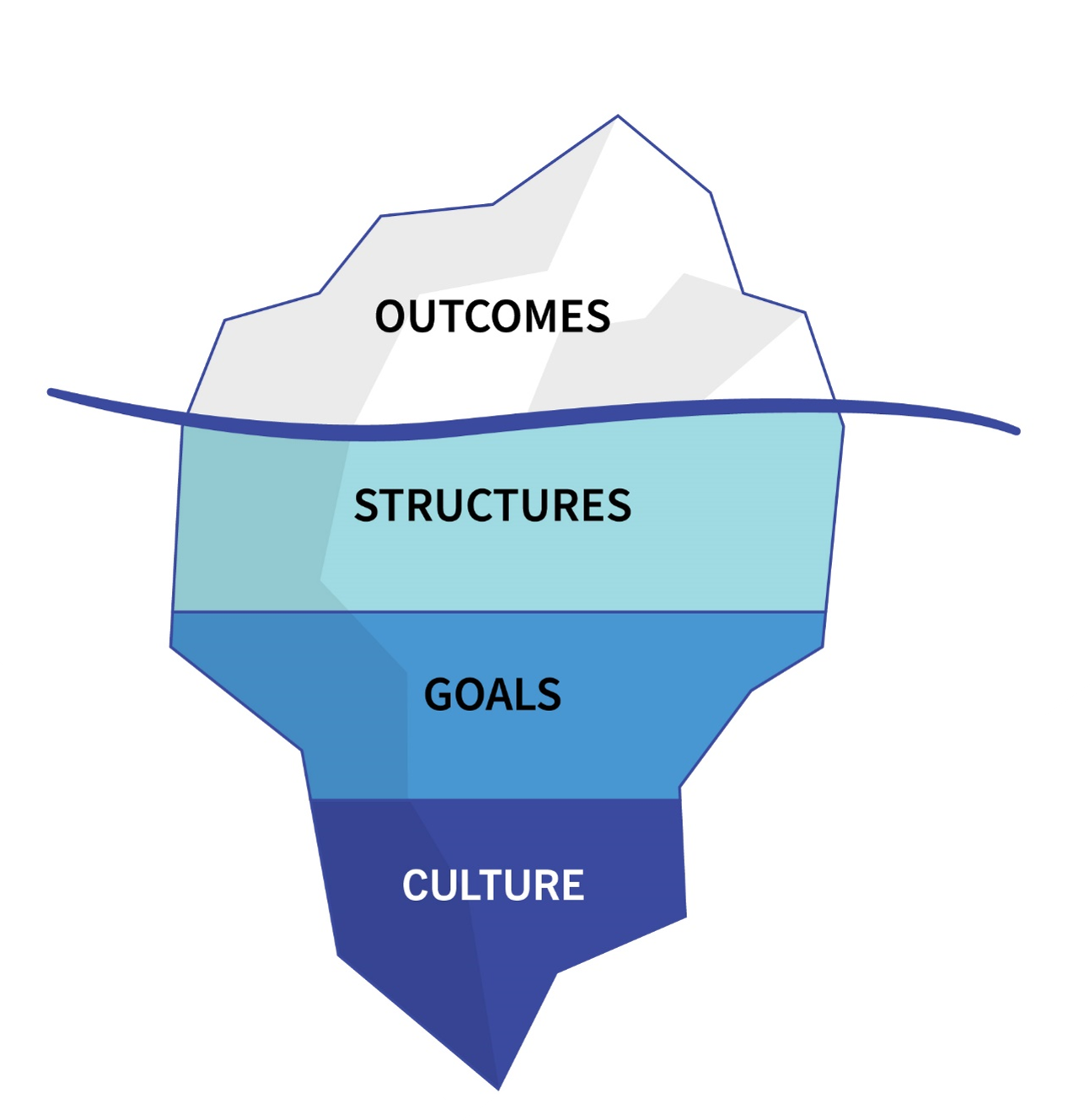

A systems thinking approach means not only looking at the breadth of the life cycle, but also the depth of the problem (see Iceberg Model). Our healthcare system is centred around patients having access to effective pharmaceuticals, and as a society we have become more and more reliant on pharmaceuticals as a societal solution to conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease that are largely preventable. Our reliance on the use of pharmaceuticals is deep-rooted and complex, and won’t be solved overnight. However, a systems thinking approach embraces this challenge and works with this complexity. It is about collaboration, co-ordination and changing culture. It is about collectively creating a long-term vision but with pragmatic short- and medium-term goals that everyone works towards. It is about understanding the big picture and working with it.

This adapted Iceberg Model considers that, like icebergs, 90% of a complex issue is hidden beneath the surface, and these underlying factors drive the visible outcomes.

We have adapted the original Iceberg Model to help us identify leverage points for change across the UK healthcare pharmaceutical system. The model considers that, like icebergs, 90% of a complex issue is hidden beneath the surface, and these underlying factors drive the visible outcomes (here, pharmaceutical pollution). In our version of the model, we consider that organisational structures and processes directly underpin the outcomes, and these structures themselves come about from the strategic goals of the organisations involved. In turn, the goals are a consequence of our societal mindset or culture. We are using this model to identify leverage points at all levels of the system, assuming the theory that the deeper the level, the more leverage that point will have.

Figure and text adapted from our Lancet Planetary Health publication.